Oklahoma and the Fearsome Spanish Influenza

- John J. Dwyer

- Dec 31, 2016

- 4 min read

World War I proved to be the most devastating experience for Oklahomans since the War Between the States. Over a thousand Sooner troops died in battle, more than seven hundred perished due to disease, another five hundred went missing in action, and over four thousand suffered wounds. History, however, well teaches that the consequences of war extend beyond the obvious to the subtle, the unforeseen, and the future.

The so-called “Great War” lasted from 1914-1918—1917-1918 for America. It generated pride, patriotism, determination, and courage on both the battlefront and the home front. But it also produced an emotional climate that spawned rampant fear, despair, uncertainty, hatred, and supply rationing even on that home front. Groups as diverse as pacifist Mennonite Christians, others of German heritage and sometimes language, socialists, would-be union organizers, and even citizens not judged sufficiently enthusiastic about the war effort were persecuted in manners ranging from trivial to mortal.

One of the most catastrophic consequences of the war emerged with the worldwide onset in 1917 of the Spanish Influenza epidemic, then called the Spanish Flu. This dread plague, referred to by some historians as “the greatest medical holocaust in history,” killed as many as one hundred million people worldwide—5 percent of the global population. It may have killed more people than the fourteenth-century Black Death, which wiped out one-third of the population of Europe. In the space of a few months, the terrifying reaper cut down over seven thousand Oklahomans, between five and seven times the number of all Sooner servicemen traditionally counted killed or missing in World War I.

The first graduating class of Morningside Hospital School of Nursing in Tulsa, 1919. The Spanish Flu epidemic caused the establishment of the hospital, which later became Hillcrest Medical Center. Courtesy Tulsa World.

The war perhaps caused the epidemic, and it assuredly both hastened and worsened it. Deriving its name from the Spanish media who apparently first heralded its disastrous implications, significant evidence suggests that it began in Haskell County, Kansas, just thirty-five miles north of the Oklahoma line, in February 1918. Ironically, the first Oklahoman to die of the Spanish Flu was Muskogee attorney Norman Haskell, son of the state’s first governor, Charles Haskell.

The next month, the disease erupted in Camp Funston, temporary home to thousands of army recruits at Fort Riley, Kansas, including Harry Bathurst of Cherokee and many other Oklahoman soldiers, including interned Mennonite conscientious objectors. According to Michael Dean of the Oklahoma Historical Society, “Because of the war, Army bases were jammed with men, causing the flu to spread with a speed never seen before.”

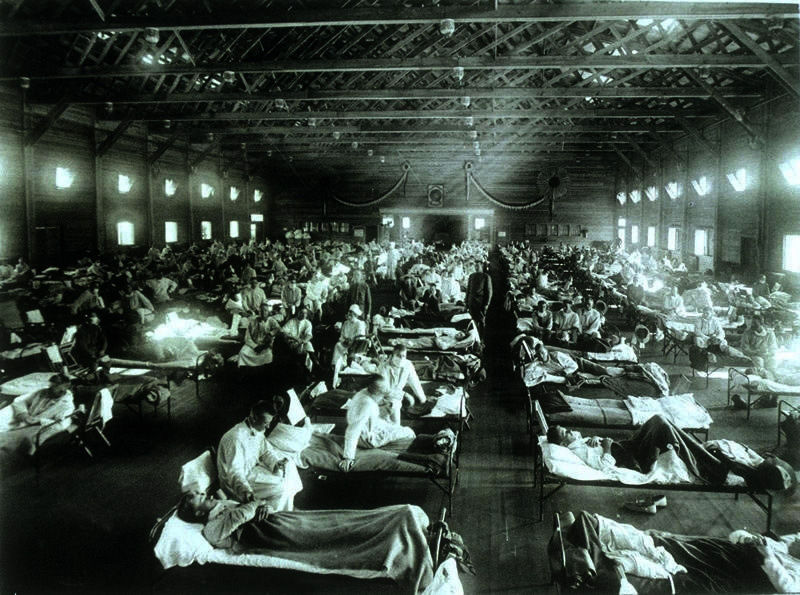

Nurses, other workers, and afflicted soldiers, some of them Oklahomans, in an emergency hospital at Camp Funston, Fort Riley, Kansas, during the 1918 Spanish Influenza epidemic. Courtesy National Museum of Health and Medicine.

"The Spanish Flu broke out,” Bathurst recalled a half-century later, “and my buddies, nearly all of them, took the flu and went to the hospital, as long as there was room (there). The hospitals became full, and they put beds in the aisles, and later on even the aisles became so full that they had to put the sick boys in the kitchens, and they had very little care, and they just died like flies."

In her 2015 article “Historical Accounts Detail Wave of Flu Deaths in Oklahoma During 1918 Pandemic,” Oklahoman newspaper reporter Juliana Keeping recalled this subsequent sequence of terror:

In August 1918, the epidemic hit America’s East Coast like a bomb. At Camp Devens, in Boston, 1,543 soldiers reported ill with influenza in a single day. In a letter to a colleague, a doctor at the post described how the flu turned into the most vicious type of pneumonia he had ever seen; the faces and bodies of dying victims turned blue from the lack of oxygen, sparking rumors that the Black Death, a terrifying plague from the Middle Ages, had returned. Healthy men dropped dead within a matter of hours, hundreds in a day, some of them bleeding from the eyes.

According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, “Influenza and (the related) pneumonia killed more American soldiers and sailors during the war than did enemy weapons.”

"The first reported case of Spanish Flu in Oklahoma City," according to Dean was a young woman named Corrine Smith who was diagnosed September 28, 1918. By October 1st, Oklahoma City doctors were dealing with more than a thousand cases of flu. Two days later, the number was 2,000.”

An additional dividend of the war was the mounting of the Oklahoma flu death toll due to the absence of large numbers of the state’s doctors and nurses who had left to tend U. S. troops in stateside military camps or around European battlefields. Spanish Influenza eventually afflicted over one hundred and twenty-five thousand Oklahomans and caused the unprecedented shuttering in late 1918 of all public gatherings, including those at churches, schools, theaters, athletic contests, and businesses.

Historian Brad Agnew’s centennial history of Northeastern State University provided a cogent snapshot of the toll taken on one Oklahoma college community, Tahlequah, by the pestilence. Extra-curricular activities at Northeastern such as athletics, campus publications, and debate ceased during the fall months, as did events around the town. The cancellation of the latter perhaps proved to be fortunate, since local newspapers were scarcely able to write about them anyhow. The Cherokee County Democrat reported, “Spanish influenza is doing its work in Tahlequah . . . . In this office not a man has escaped. Extra help cannot be procured.”

Perhaps the most ominous indicator of the horrors the flu unleashed lay in the town’s mortality rate. During the two months just prior to its onset, August and September, eight and five people, respectively, died. The death toll skyrocketed as high as six times the normal number for the next four months: 22, 29, 19, 30, and 20.

Comments